To print, or not print?

One of the adverse side effects of the lockdown in India is that economic activity has slowed down completely. People used to go out and spend. But now they are stuck at home, leading to a large drop in demand in almost all sectors of the economy.

Companies no longer have demand for their goods and services, and so are laying off employees. One estimate of unemployment is that 14 crore people have lost their jobs in India over the last two months. [1] This is unprecedented in Indian economic history after independence, and is probably the worst economic situation in many years.

Government tax revenue is dependent on economic activity. When economic activity falls, government revenue also drops. In this economic environment, tax revenue is likely to fall sharply this year. The government has to find alternative ways of ensuring that it has enough money to pay for spending this year.

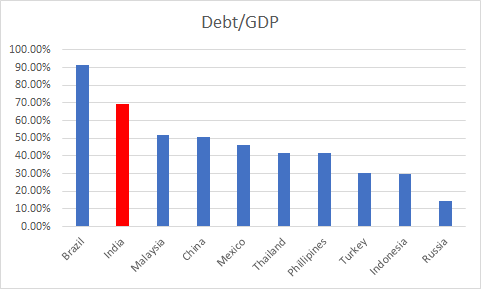

This means that the government has to borrow to fund its expenditures. But over the last few years India has borrowed a lot. India’s debt to GDP ratio is the second-highest among emerging market countries at 69%.

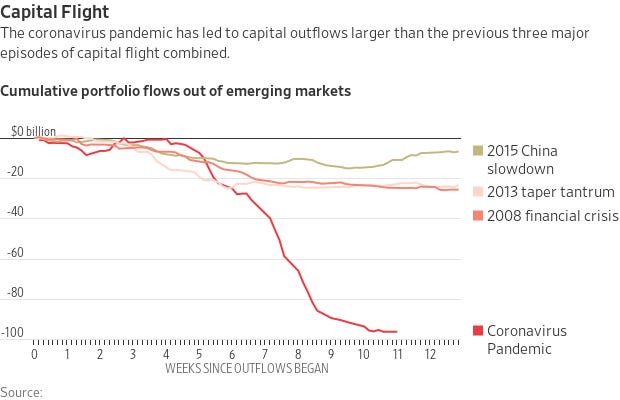

Because of the economic slowdown (which happened before the pandemic), the government has failed to meet its fiscal deficit targets over the last few years. Along with that, foreign investors are reluctant to put money in developing countries like India, because they are concerned that they may not be able to pay their debts back.

This is particularly worrying for the government as it gets money to spend from issuing bonds to investors. If that money stops flowing, then it means that the government has to either lure them back with a higher interest rate on the bonds or, not spend the money. This is already happening as investment flows to developing markets have reduced by $100 billion.

Source: WSJ

To make things worse, India does not have the best credit rating. It is rated Baa2, which is just 2 levels above junk status. That means that if the credit rating agencies think that Indian government bonds are not a safe investment, they will downgrade it and international investors will not invest in the government bonds.

As you can see, it is hard for the government to finance its expenses this year. It has one option left: printing money.

Printing money: Walking on a tightrope

When money is printed explicitly for the purpose of funding government expenditures, its called deficit monetization.

In most countries the control of the money supply is given to the central bank. This is to ensure that it is done without political considerations, and in the long term interests of the economy unlike politicians who have to face elections every 5 years.

Central banks don’t normally print money to fund government spending. This is a no-no in the central banker rule-book as it usually leads to high and unpredictable inflation.

But this time, the central banks might be forced to do it by circumstance because there is no other way to fund government expenses. This can go in two (of many) scenarios:

The optimistic scenario

The RBI prints money to fund government spending. The government spends money to ensure that everyone has food to eat, money to spend on essentials and so on. Then the government’s tax revenue recovers, it buys back the debt from the RBI and the money supply comes back to normal.

But this is the most optimistic scenario. Many things can go wrong in this.

In general when the money supply rises faster than the production of goods and services in the economy, prices increase.[2]

So, if the RBI prints money at a faster rate than the rate of goods and services produced, then prices rise. Government expenses are likely to be far higher than previous years and government revenue is likely to be far lower.

This means that the RBI is likely to print money at a rate faster than the rate at which goods and services are produced. That can lead to inflation that is high and unpredictable, making the problems worse than they are now.

The pessimistic scenario

The RBI prints money to fund government spending. Inflation sky rockets, and people become less confident to spend and invest because of the uncertainty over the economy. This leads to more government spending, more deficit monetization, and the cycle repeats.

The RBI today is forced to chose between two of its objectives: low and steady inflation, and short term macroeconomic stability.

If the RBI does not monetize the deficit, then it faces the possible collapse of incomes in India for the short term. This would mean that far more people lose their jobs, fewer goods and services are produced, and the economy goes into a tailspin.

But if the RBI does monetize the deficit, and it goes poorly, that scenario is as bad as, if not worse than the above scenario. If government spending is ineffective at reviving the economy, or is wasted in low impact schemes, then India will face both problems - low growth and inflation.

Shaktikanta Das faces a dilemma here: to print or to not ?

The answer to this will determine the future of a billion people.

[1] That is an unemployment rate of 26%. This is the same rate as the US during the Great Depression.

[2] The actual causes of inflation are greater including inflation expectations, bank lending rates and the velocity of money. But as an approximation, this holds true.